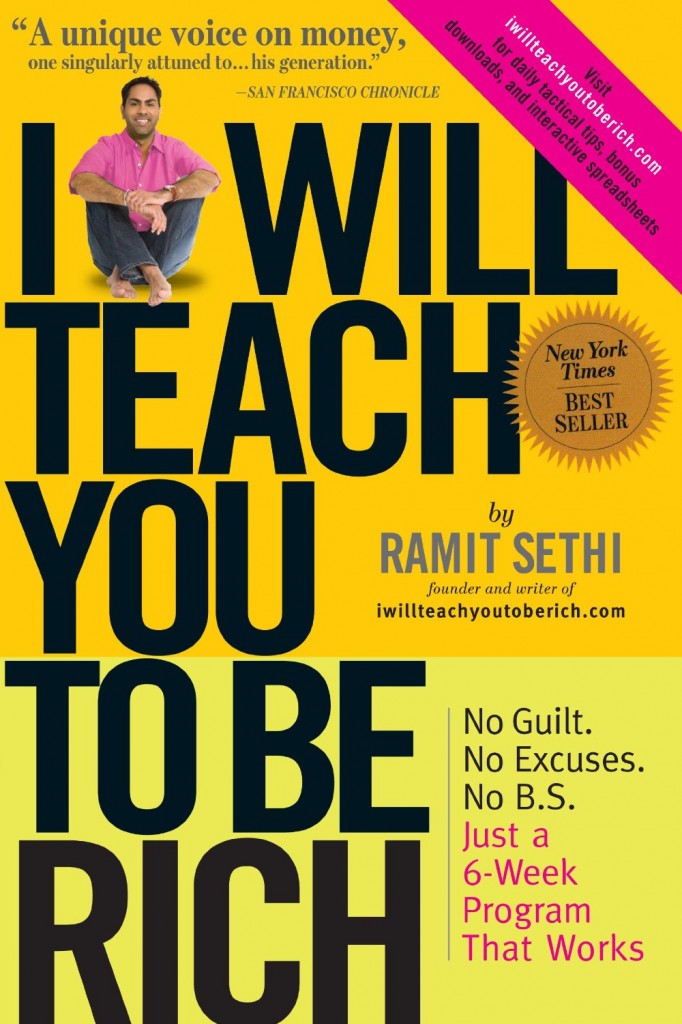

I Will Teach You To Be Rich by Ramit Sethi is a book about very slowly getting rich. In many ways, it’s almost exactly the opposite set of advice as what you’d find in Timmothy Ferris’ The Four Hour Workweek. You could say Sethi sees life ideally lived like this: work and save, then live, then die. While in contrast, Ferris thinks people should work and live and work and live and work and live and then die.

I Will Teach You To Be Rich by Ramit Sethi is a book about very slowly getting rich. In many ways, it’s almost exactly the opposite set of advice as what you’d find in Timmothy Ferris’ The Four Hour Workweek. You could say Sethi sees life ideally lived like this: work and save, then live, then die. While in contrast, Ferris thinks people should work and live and work and live and work and live and then die.

I don’t care to take up too much of this book report comparing the philosophies of financial self-help writers, but I think I agree with Ferris most of the time. There are just too many things I want to do, that I’m sure I won’t want to do later.

Ramit’s road to riches is probably a reliable one. It’s slow and consistent and clearly ‘under control’. A lot of it is tweaked or updated classic financial advice. Things we’ve heard, but for whatever reason ignore. However, Sethi is effective. As an example, since I began reading the book earlier this week, I cut nearly two years off the length of my car loan.

Part of what makes Sethi effective is his command of humor. He uses it just enough to break up the monotony of the otherwise bland topic, and to better crystalize the weight of a concept. A lot of his jokes revolve around his Indian heritage, and he plays on the whole guru stereotype. He’s humorously abrasive and it works. Though it makes a mockery of the tagline “No guilt”. There’s a ton of guilt, it’s just funny guilt.

In The Book

In the first chapter, Would You Rather Be Sexy, or Rich?, Sethi argues that if your goal is to be rich, although being a fancy stock trader on wall street would be sexy, it’s an unlikely way to get to your goal. He also uses the opportunity to point out that being rich is sexy. The problem is, I’d imagine most of the people drawn to a book about how to be rich are less interested in the security money brings, and more interested in the luxury and power. This is a book about security and then luxury and not really about power at all–except for the little section about getting a good deal on a car.

In the second chapter, Sethi discusses optimizing credit cards, which among other things, involves reducing interest rates, eliminating yearly fees using his negotiating tactics, and getting the debt ratios under control (you should use less than 30% of your available credit). He also says that most credit cards will warranty purchases you made with them. Low and behold, he’s right. Though it sounds like a pain in the ass.

At the end of the chapter, Sethi goes into some basic debt elimination principles. His advice is good, however, I think for someone who needs a book to help them get out of debt, How to Get Out of Debt, Stay Out of Debt, and Live Prosperously by Jerrold Mundis is a better choice.

Chapter 2 is about getting the best out of banks. It was affirming to read Sethi’s feelings about bank fees. Their existence is an insult. So, he advises readers to move their money to the new school of online bank accounts that are usually free. I am in the process of doing this myself. Goodbye, Bank of America. I hope you’re out of business soon.

In the same chapter, he also strongly urges the use of a savings account as part of “conscious spending”, which he goes into a couple chapters later. Since money will sit in a savings account while it’s accumulating for some particular purpose, a high interest account can at least offset the cost of inflation. Again, he suggests an online savings account, since the savings account at the local bank probably offers virtually no interest.

Chapter 3 is about investing. This chapter brought some clarity to the concept of investing and diversification as an adult. I’ll admit, it’s been a mystery. Sethi took time to explain the workings of riskier trading and investing, but in the end suggests people put their money in a variety of different kinds of accounts, and either an index fund or a lifecycle fund, both of which respond to the broader market, rather than any individual company.

In Chapter 4, Sethi introduces his concept of conscious spending. He summarizes it himself saying “Spend extravagantly on the things you love, and cut costs mercilessly on the things you don’t”. Think of the folks who always skip getting a coke at a restaurant in order to save money, but don’t bat an eye at a $15 bank maintenance fee. No one loves bank fees, but a lot of people like Coke. So why don’t they get Coke when they go out to eat, and stop paying bank fees? Sethi argues that they’re just not conscious of how they’re really spending money and gives commensurate advice to help solve the problem.

Chapters 5, 6, 7 and 8 go into the nuts and bolts of growing and automating the investment system he recommends we begin building in chapter 3. First he dispenses with the myth that brokers are affective–apparently they almost always fail to ‘beat the market’, in other words, they fail to make more than the total market average. He also tackles some of the psychological blocks people face–such as not having enough time, or not “getting it”. This was a good read, but admittedly a few steps ahead of my current stage.

The final chapter, A Rich Life, comes from reader’s common questions about saving money, such as, “Should I pay down my student loan, or invest?” and “We’re all hypocrites about our wedding”. It was worth reading, but the most broadly useful advice is in pages past at this point.

In Conclusion

It’s solid advice, it’s funny, and it’s easy to read. Sethi never fails to tell you what he thinks you should do, which is a turn off for some. But for me, it actually makes it a bit easier to compare philosophies and therefore more effectively come up with the best course of action for me. In my view, I think I’d rather work forever and spend my money on opportunities now, rather than save a ton to retire and look for opportunities then. That been said, Sethi brought a clarity to the situation that challenges that ideology, at least in some cases.

The book is written for people in their 20’s. If you’re in your 20’s and feel confused about money, read this book. You will not feel so confused about money anymore.

Recent Discussion