William Petruzzo used to hate reading. It was tedious, and boring, and time is such a precious thing to waste on thinking. One day William Petruzzo loved reading. Books and shampoo bottles and websites. Books about God, and about books about God; Shampoo bottles about chemicals, and websites about the future. William Petruzzo liked the way his talking sounded more when he read his books and shampoo bottles and websites about the future.

William Petruzzo believed the books he read, because they told him they were real. Sometimes William Petruzzo would say, “This book must be out of its mind!”, because it said something a little different from the last book. So it goes.

Everyone knows: William Petruzzo knows.

One day a book lied to William Petruzzo. It said this happened, and this happened, and this happened. That this person was that person. That there were two people when there was only one. That there was a party, and a war and a spaceship.

William Petruzzo liked the lies. “The lies were poets,” Said William Petruzzo, just now. “It’s a beautiful way to describe fiction,” William Petruzzo thought to himself, imagining how pleasant the words he just wrote would look between quotation marks. “Truths were bureaucrats,” He said, stretching the limits of reasonable metaphor.

William Petruzzo heard lies about a boy in a desert. Then about the persons and places of Malacandra, Perelandra and Earth. He heard lies about actors and teachers and superheros. The dead coming back to life and the living never really living.

“Lies, lies, lies!”, William Petruzzo would sometimes say when someone suggested that he listen to a lie he didn’t like. William Petruzzo hated when anyone lied to children about magic. So it goes.

“Believe some of Kurt Vonnegut’s lies,” Said Nathaniel Tyson, from beneath the hardy red facial hair of a young sorcerer.

“Here, here!” chimed Daniel Ballard, wrapped in a sports blazer of manhandling charm.

William Petruzzo thought long and hard about whether to talk about Nathaniel Tyson and Daniel Ballard. He wondered whether he would talk about bureaucracies or poems, and whether his execution was as ostentatious as it sounded when he read it just now. William Petruzzo still remains undecided.

“Breakfast of Champions, is it?” Piped Nathaniel Tyson.

“Hardly, it is another.” Retorted, Daniel Ballard.

“Slaugterhouse-Five”

“Yes”

“Yes”

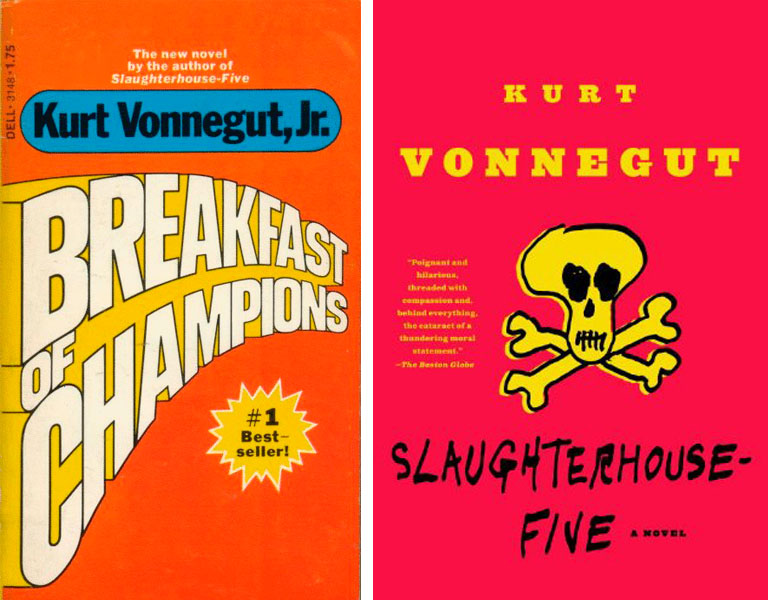

With delightful, bureaucratic inefficiency it was decided that Kurt Vonnegut’s most notable lies told were titled Slaughterhouse-Five and Breakfast of Champions.

The artwork for those lies looked like this:

Beautiful Lies

William Petruzzo read all those lies on something called a “book” that looked like this:

“Book”

William Petruzzo loved the way Mr. Vonnegut told a lie. Like he was wasting his time, but that’s all he was ever asked to do anyway.

Mr. Vonnegut told a lot of lies about death. William Petruzzo was already in a farting match with death’s stink when he read Mr. Vonnegut’s lies. Sometimes William Petruzzo felt that Mr. Vonnegut may not be lying to him after all.

“Kurt Vonnegut was a bureaucratic liar!”, He would say after confusingly repurposing words in some banal writing exercise.

Later, in the present, William Petruzzo would learn that Hollywood tried to tell Mr. Vonnegut’s lies in the year 1972. This is what it looked like when Hollywood tried, after it was chopped up so that it cannot be understood:

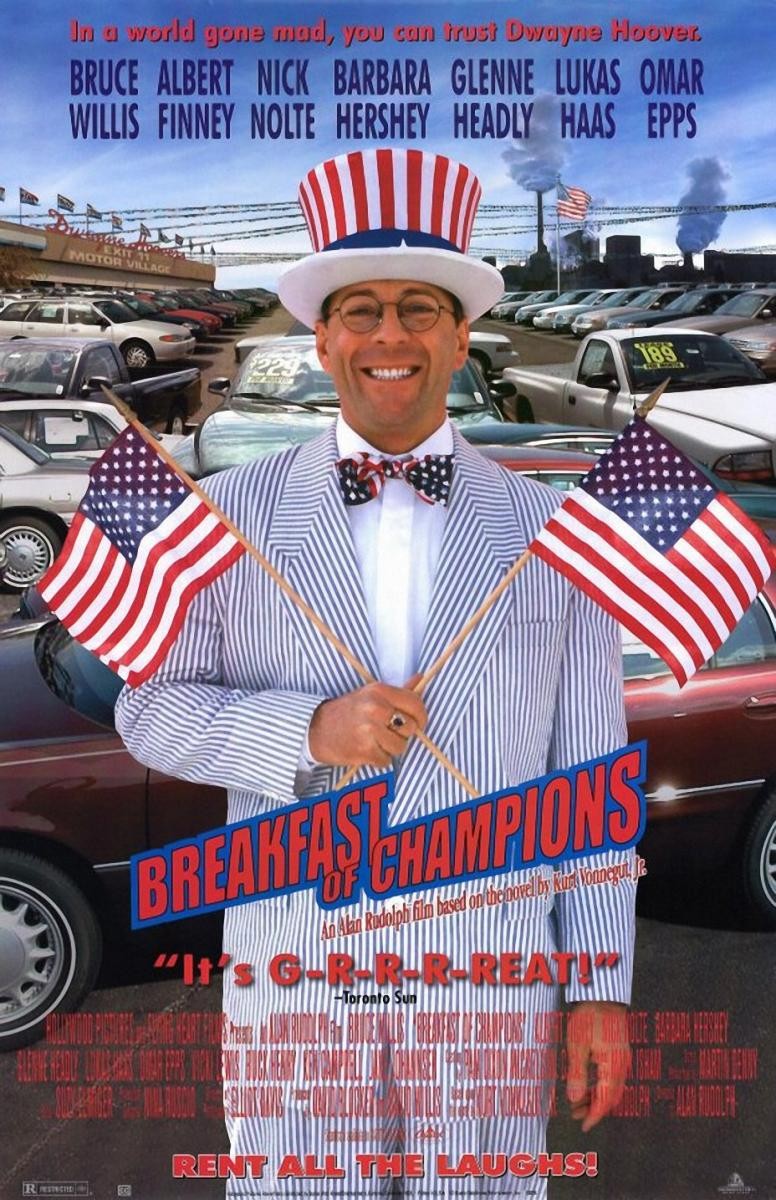

Bruce Willis is a man in Hollywood who pretended to be Dwayne Hoover in the year 1999. Dwayne Hoover is a lying bureaucrat that Mr. Vonnegut told William Petruzzo about. This is what it looked like when Mr. Willis pretended to be Dwayne Hoover:

~

William Petruzzo did not see Dwayne Hoover, he only heard about him in all the lies he read. Later, in the future, William Petruzzo will listen to how Hollywood had told Mr. Vonnegut’s lies in the past. His feelings about the lies are still trapped in the future. William Petruzzo’s websites about the future are telling him beautiful lies about his feelings there.

William Petruzzo became exhausted with lying.

“Who will understand,” he would probably think to himself right now. “Someone, maybe, eventually,” he would add feeling the need for a few more words.

Seconds later, in the future, William Petruzzo will bureaucratically categorize what he’s written here and and make quiet note to himself that this is an annoying way to review a book. Then he’ll press the “publish” button.

Publish.

Recent Discussion