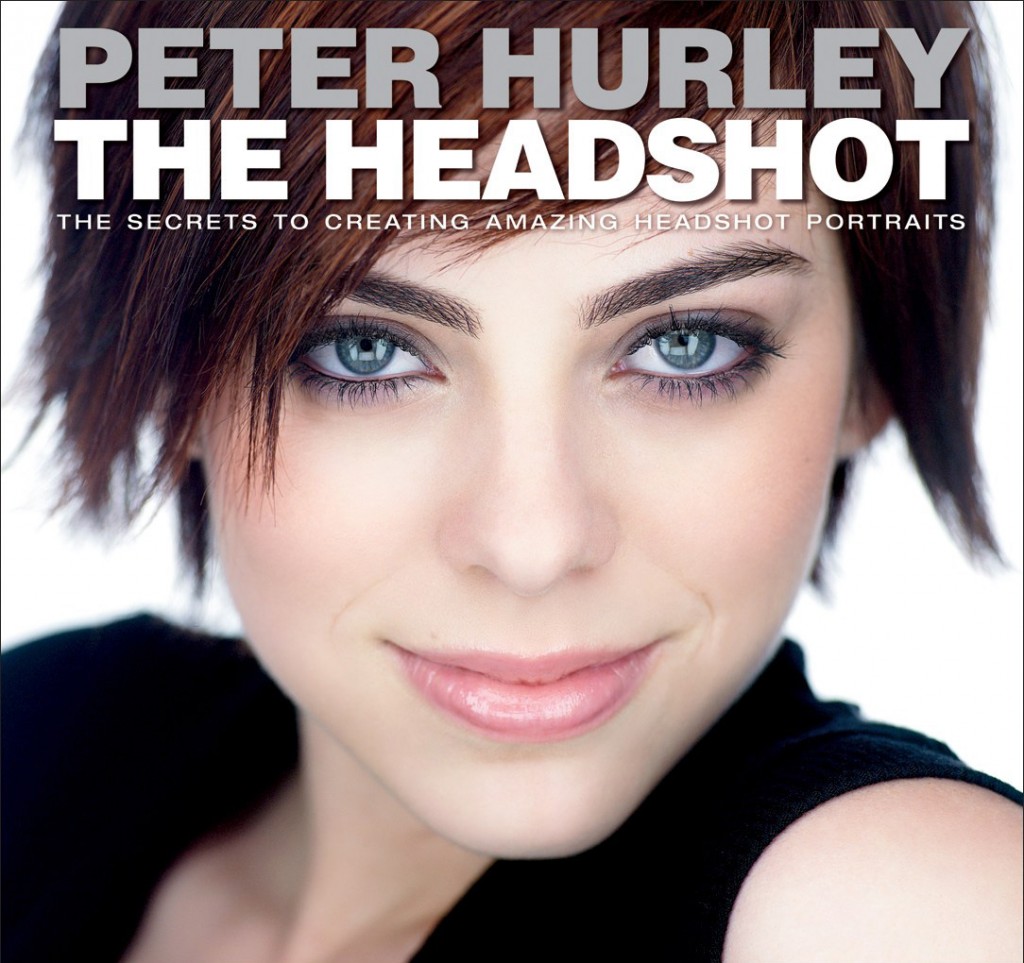

The Headshot by New York headshot photographer Peter Hurley was a pretty delightful blend of practical technique while shooting, and mindset while interacting.

The Headshot by New York headshot photographer Peter Hurley was a pretty delightful blend of practical technique while shooting, and mindset while interacting.

When you have been working with portraiture for 10 years, you learn a lot about how to interact with subjects, and what to expect from them, and you learn a lot about what you want to create. I wish I’d read something like this earlier because I could have skipped a lot of trial and error.

The Headshot rolls through pretty much all the major bits of creating headshots. It covers Peter’s philosophy, which largely revolves around diverse expression, as you might expect from someone working with actors and CEO’s all day. It covers the technical aspects of headshot photography, although heavily assumes you know what you’re doing with light and camera functions, and it pretty strictly looks at how Hurley likes to do things; he has an aversion to dramatic shadows.

The Headshot discusses the power dynamics and judgmental mindset of a portrait photographer, something Hurley calls Sherlock Holmesing–noticing all the things that it might be inappropriate to notice in normal discourse. I suspect that this is a valuable section, especially for the fledgeling photographer who hasn’t yet differentiated their patterns of speech when wearing their photographer’s hat. If you want to make someone look good, you have to be able to address those things about them that do not look good. Without your photographer badge, you can’t talk to someone about their lazy eye or double chin. But, if you really want to create a stellar image of them, you’ll need to address it.

About the second half of the book, in a broad sense, covers direction of subjects; principled techniques which can be used to discover and pull the best out of a subject. But in there, there are two bits of advice which Hurley sees as absolutely central to excellent headshots. Those are “squinching” and defining the jaw line. He produced two videos which cover these topics just as well, if not better, than the book. But both of them, I sense, are overcooked for my taste.

Squinching is essentially a very mild squint. It’s narrowing the eyes primarily using the muscles around your lower eyelids. It’s the pretty classic high-fashion look, and it helps the subject look engaged and more expressive, like they’re really paying attention, but also sometimes looks like they’re trying too-hard (such as in some of the photos of Hurley himself). People have difficulty following this instruction without some significant coaching beforehand, which Hurley goes to some lengths to explain how to do. The move which helps define the jaw line is less easily explained. It’s something like sticking your head foreword like a chicken, blended with some leaning in this direction or that direction.

When I’m shooting headshots, I give instructions for squinching and defining the jaw line also, but I find these to be less central concepts to my work. Someone who doesn’t respond to coaching their eye movements usually just end up looking unnatural unless you really spend an inordinate amount of time with them. And, if they’re not responding to the coaching, I find there’s usually a faster way to get a great expression. Similarly, defining the jaw line often weakens the appearance of their neck (as seen in the cover of the book), which I’m not a huge fan of. I would generally prefer a strong neck to a strong jaw line.

One of the most valuable considerations I took from Hurley’s book was that of expressive subtlety. For about 8 of the last 10 years, I’ve focused on photography which is personal in its purpose. I have been photographing people mostly for the sake of their families and friends. When those people look at an image, they want to see that person at their most authentically happy. Big toothy genuine smiles, gums, double chins–it’s all fair game, as long as the expression is one of honest happiness. But for all other purposes, where the image is taken for the sake of someone who doesn’t necessarily know the subject, subtlety is absolutely essential.

Hurley’s book definitely helped to activate my mind to pay attention to the subtle expressions and to consider how to best coax those out of my subject. I differ from Hurley on some ideological level, though. Where Hurley is always shooting for his portfolio–perhaps the better approach–I am always shooting for my subject, or my subject’s audience. The result is often the same, but for me, how I get there must feel authentic to the subject.

The Headshot was an excellent read. I think it is likely a better book for a semi-seasoned photographer, than one just starting out. And the reason being that photographic intuition takes a huge amount of focus at first and it takes time before a photographer can both focus on the photography itself and the subtleties of the subject before them. My advice would be to shoot shoot shoot until your working the camera automatically, and thus have enough headspace to move focus to the finer details of the subject.

Recent Discussion