![Ready-for-Anything-Productivity-52-Principles-for Getting-Things-Done [Review]](http://www.williampetruzzo.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/Ready-for-Anything-Productivity-52-Principles-for-Getting-Things-Done-Review-676x1024.jpg) Ah, good old 2004. I would have recently graduated high school, if I had felt that was something worth my time. And, It might’ve been, but not for being completely out of step with the way I was going to internalize information; probably some angst related stuff too. It was a time when the Western World wouldn’t have so unanimously thought there was anything tacky about a book title like “Ready for Anything: 52 Productivity Principles for Getting Things Done“. I, on the other hand, would have rolled my eyes so hard, I might’ve gone blind. But I was a bit of a shithead, I’m sure.

Ah, good old 2004. I would have recently graduated high school, if I had felt that was something worth my time. And, It might’ve been, but not for being completely out of step with the way I was going to internalize information; probably some angst related stuff too. It was a time when the Western World wouldn’t have so unanimously thought there was anything tacky about a book title like “Ready for Anything: 52 Productivity Principles for Getting Things Done“. I, on the other hand, would have rolled my eyes so hard, I might’ve gone blind. But I was a bit of a shithead, I’m sure.

Of course, I’m grown up now and the rolls are reversed. I get a lot of inspiration out of the books I read and here I find myself wishing this book had a title that could be more easily taken seriously. The 17 year old hiding inside me is getting a headache from all the eye rolling.

I’m having that trouble a lot these days. When I write a book, I promise not to give it a stupid name. Probably something like Not a Stupid Name for This Book by William Petruzzo. Don’t click on that link, it goes to the future.

Okay, back to David Allen’s book. Its contents are more well stated than the titles themselves.

This is like a daily devotional for personal productivity. There are 52 sections, each about 2 – 5 pages long. You could keep it in your bathroom. This book is a part of the ‘Ready for Anything’ series and the first of the series I have read. Perhaps it would have been better to go in order.

Nonetheless, this book came with very few ‘huh!’ moments for me. “Well that’s interesting” moments. “I never thought of that before” moments. I suspect this may be true for most people who read it, or at least for the chronically introspective. The advice Allen gives and the observations he makes are mostly concerning the personal friction in our lives.

Clearing your head so you can think about your responsibilities and commitments (he uses the term Psychic RAM a lot and its kind of distracting). Achieving focus that’s actually useful. Find your own structures and processes that can remove the most cumbersome ‘thinking’ tasks we have. Developing proactive and reactive ‘muscle memory’ so that we can be relaxed while still acting decisively. These are the broad strokes Allen take a fine brush to.

So, much of it is familiar. But, where many of us have a sense of these things, Allen provides a clear perspective. Not the definitive perspective, but a useful one nonetheless.

There were a couple concepts that popped out at me and caused me to really reflect in a new way.

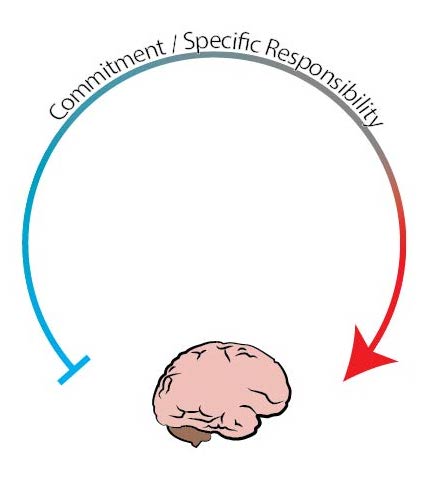

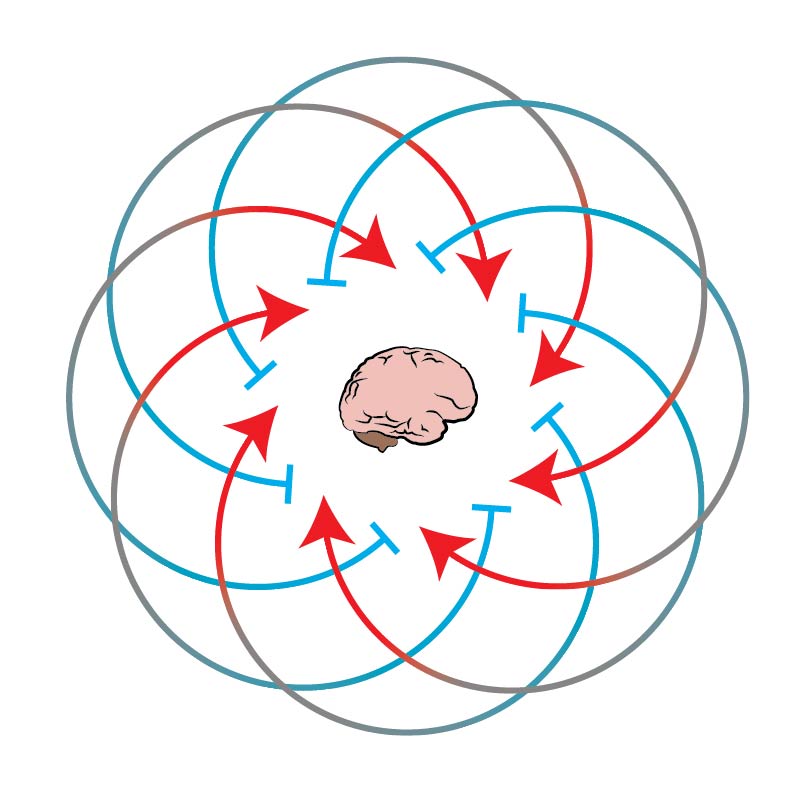

Mental Loops are a way of thinking about our commitments, obligations or needs. The more ‘loops’ we have open, the harder it is to figure out what to do next in any particular direction. We can keep the loop moving by determining the next action and taking it (or setting sufficient reminders in life that it will be taken predictably in the future). Or we can close the loop by fulfilling the commitment completely.

Loops, Allen says, will stay open until the commitment is completely fulfilled. The diagram I created below shows the process. The line represents the commitment. We are at ease as the commitment is accepted, but it can eventually work its way into confusion before it gets done.

An example: committing to taking some clothes to the thrift store for my sister. If I take that commitment and simply juggle it in my head, it will compete with everything else I have to do and I’ll move along that line until I’m anxious about it, or it’s having some negative effect on me, at which point I might finally act and fulfill the responsibility. The loop is simply staying open and degrading the experience of life until then.

And it’s easy to see how that might start to cause a lot of confusion and anxiety.

Allen is basically arguing for outsourcing brain power. My subconscious mind shouldn’t have to juggle the question of whether I’m going to fulfill this commitment. So, where loops stay open on their own and eventually begin to torment us, we can move all that energy somewhere else. While fulfilling the commitment closes the loop, so does simply determining when, where, and how to fulfill the commitment, with ample reminders to do so.

I also appreciated Allen’s take on “getting organized” which could provide some interesting insight into our less than conscious feelings.

When you really want to have or experience something, what you know you must do to get there is seldom viewed as “getting organized.” It is just done. When you “have to get organized,” you’re probably not appropriately invested yet in what you need to get organized for.

That’s a bit of a challenge, but it resonates with me. People are remarkably good at figuring out how to do the things they want to do.

In Conclusion

I may or may not delve into Allen’s other books. It was an excellent refresher for me, since I haven’t read much of this sort in several months. The short chapter format, I think, is excellent for people who want to read, but have difficulty committing so much time right away. It was about $10, I think. I’d say I got my money’s worth.

Recent Discussion